Kalason Oto: Singing Bus Horns in West Sumatra

Sound: Kalason oto (often simply “kalason”)

Location: Alahan Panjang, Kab. Solok, West Sumatra

This post is dedicated to Pak Budahar - a real Minang musical legend who literally spread music across Sumatra, providing sweet solace to his passengers for decades. Next time you honk your horn, I hope you think of him.

+++

What was the last time you honked your car horn? If it wasn’t a precautionary toot, it was surely out of frustration, if not outright anger. The honk is a scream from within our sealed-in vehicles - “Take heed! There’s a human in here!” But have you ever honked with tenderness, with love, with longing? The tukang kalason of West Sumatra have.

The Minangkabau people of this region are famous for their tradition of marantau, immigrating far and wide in search of a better life (often opening nasi Padang spots wherever they go!) Back in the 1950s, buses journeyed overland carrying migrants from West Sumatra to ports across this massive island - Medan, Pekanbaru, Bengkulu. This was an emotional journey: as they left their village, they looked onward to their future life with trepidation, then looked behind with longing at the home and family they were leaving behind. As the bus climbed the mountains and away, the tukang kalason would play the sweet sounds of home on his musical horn.

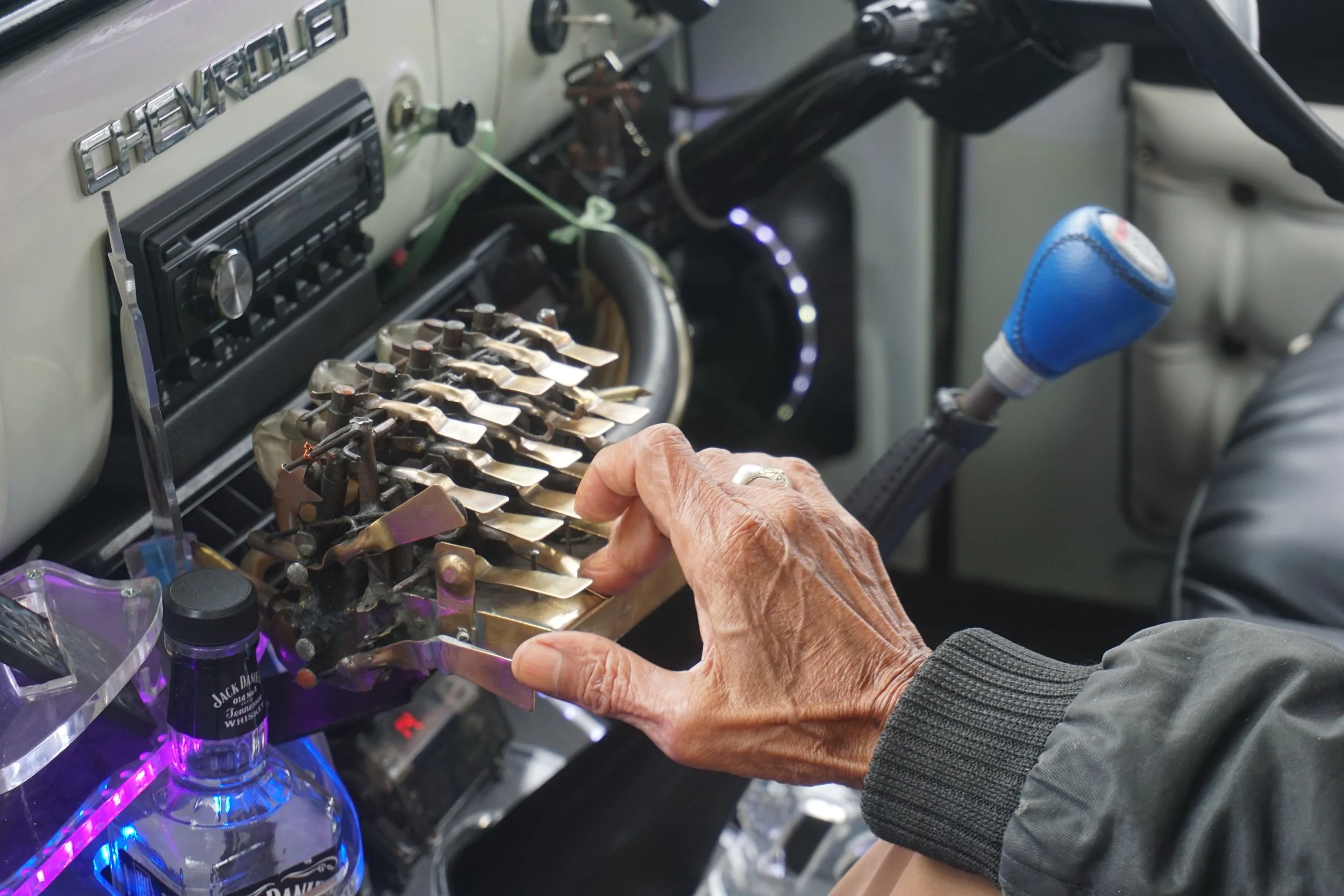

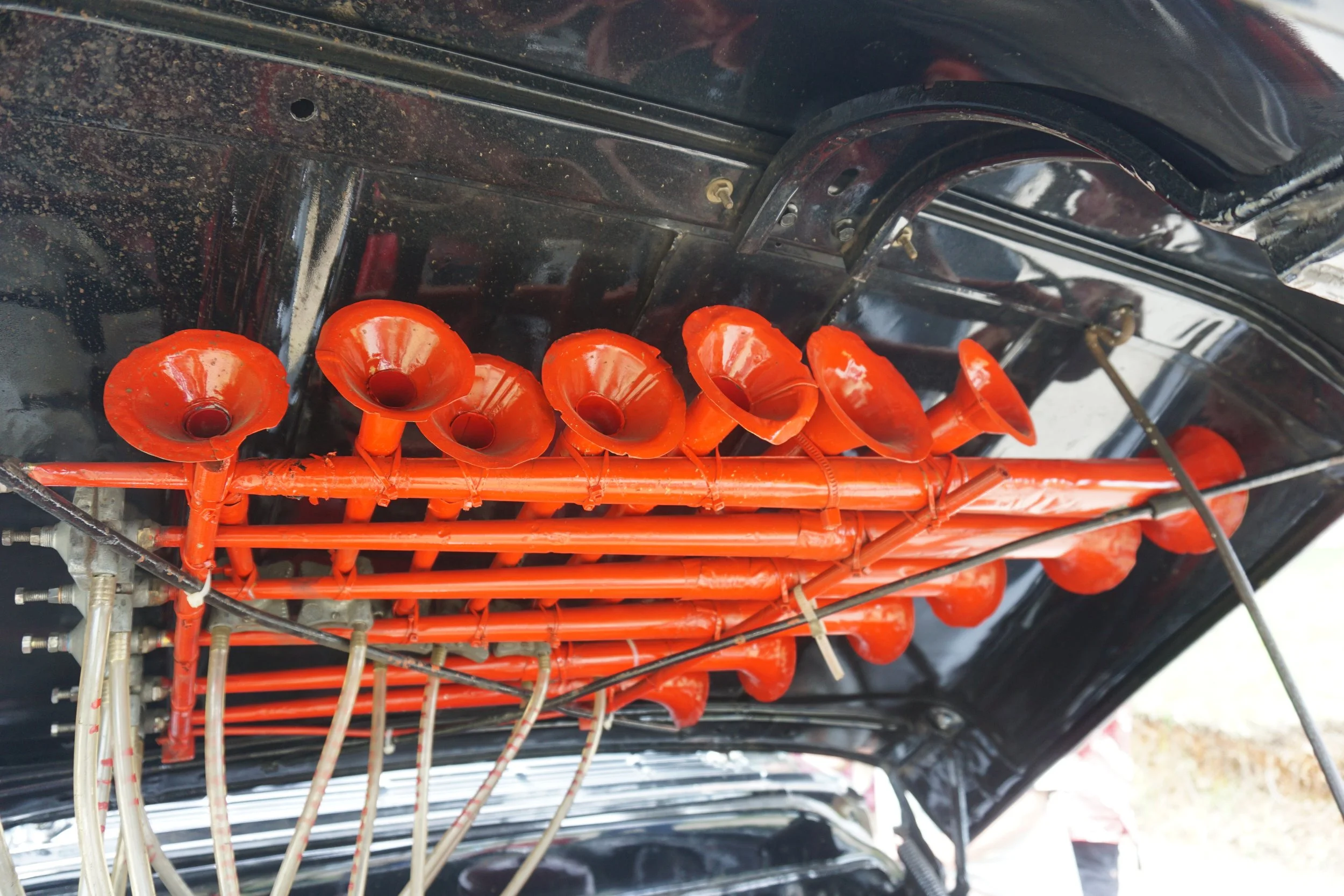

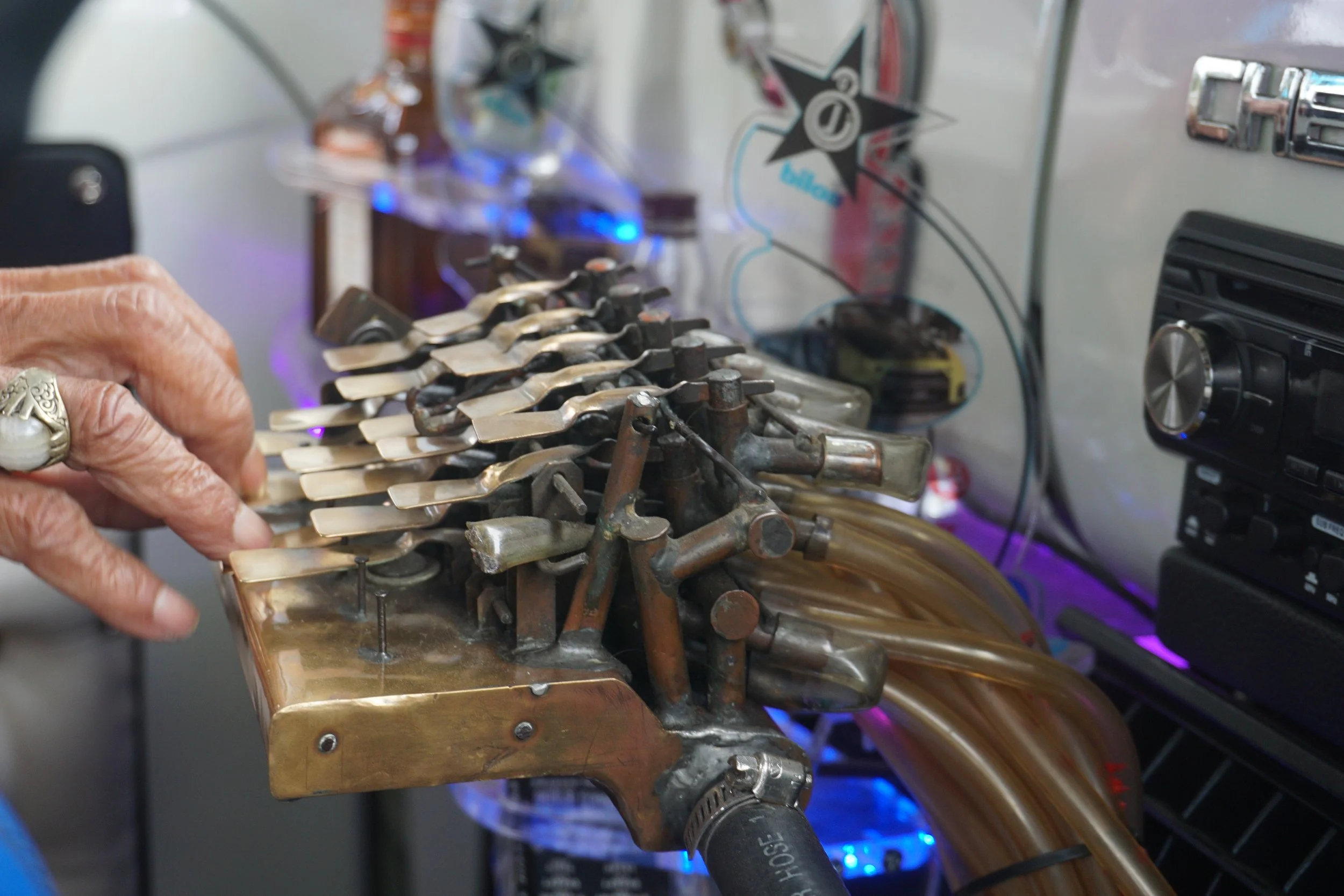

Some genius Minangkabau mechanic had armed the buses with a remarkable tool: a kalason oto (literally “car horn”, from the Dutch claxon) which didn’t just toot but sang! After Indonesia’s independence in 1945, American car manufacturers like Chevrolet began importing buses to Sumatra. Under the hood were car horns typical of the time: a few metal or plastic trumpets (trompet or corong) with reeds that would sound out a phrase (what Indonesians fondly call telolet!) when air was sucked through them via the carburetor. A mechanic in the highland town of Bukittinggi collected spare horns and had the bright idea of tuning and arranging them in a musical scale, then routing them to a typewriter-like keyboard (kontak or tuts) beside the steering wheel for the driver to play.

At first, these kalason had eight notes - just enough for an octave in the more or less diatonic scale used for playing the sweet, ornament-rich melodies of Minangkabau folk music. As this new feature caught on, though, it was developed even further, with 14 notes becoming common, even up to 24, providing even more flexibility for the driver who would often sing along - multiple octaves allowed them to find a tune that fit their range! Left hand on the steering wheel, right hand on the kontak, the drivers pioneered a one-handed playing style that combined the inflected melodies of Minang music (especially those of saluang flute music and rabab fiddle) with rhythmic accents and chords (garitiak - like a musical garnish*) perhaps borrowed from the harmonium and accordion sounds of hybrid Sumatran musical genres like gamat and orkes Melayu.

+++

Dutch-era buses in Lampung - years later, these types of buses were where kalason were installed. Image courtesy Collectie Wereldmuseum (v/h Tropenmuseum), part of the National Museum of World Cultures

It was 1960, and Pak Budahar was just 11 years old when his older brother started driving for one of these Bukittinggi bus companies. Every day his brother would pick him up from school in the bus, perhaps honking out a melody to signal his arrival. They’d take the bus to the car wash and while it sat getting hosed down, Pak Budahar would try his hand at the kalason — what a sound!

Soon enough, the owner of the bus caught wind of Pak Budahar’s burgeoning talent and convinced him to join his brother as a tukang kalason, a dedicated horn player. By that time, maybe some folks had realized that it was best for the drivers to keep their focus on the road, so some had shifted the keyboard to the center of the dashboard, allowing another employee to sit beside him and provide the tunes. “I didn’t want to work in the fields, I didn’t want to go to school, so off I went!” Pak Budahar described with a wistful smile. Joining his brother on drives across the island, he had all the time in the world to hone his new craft. “As time went by,” he said, “month by month, my fingers got nimbler and I learned more and more songs.”

Thus began a decades-long career as a tukang kalason. The young Budahar was soon poached by bus companies across the region after hearing his talent, and he was making money that other teenagers could only dream of! At the same time, he got to see the world, or Sumatra anyway, driving to far-off ports through the jungly mountains of Riau, North Sumatra, and Bengkulu. Trips that these days take a few hours would back then sometimes take days over pothole-filled roads and dirt tracks that would turn to mud in the rainy season. Sometimes, the bus would get stuck in a rut in the middle of nowhere and everyone would have to hunker down for the night, cooking by the side of the road and sleeping in the bus as the jungle came alive around them.

Those long drives were like a dream. Harrowing switchbacks like the famous Kelok Sembilan (“Nine Bends”) on the way to Pekanbaru were the perfect place for performance, as the buses would slow to a crawl, allowing the sound of the kalason to better pierce the cabin. Already homesick, passengers would request local folk tunes and modern Minang pop hits, keeping tukang like Pak Budahar on their toes as they filtered those melodies through the developing kalason idiom. At some point, playing kalason became second nature. “Even when dozing off to sleep by the wheel, my fingers would keep on playing!” Pak Budahar told me with a laugh.

By the 1970s, passengers began expecting a kalason in any bus they took, even waiting days until they could get a ride on their favorite bus with their tukang of choice. The sounds of kalason whizzed by every village in West Sumatra as the buses made their way through the countryside, becoming a phenomenon that folks would wait on the side of the road just to hear.

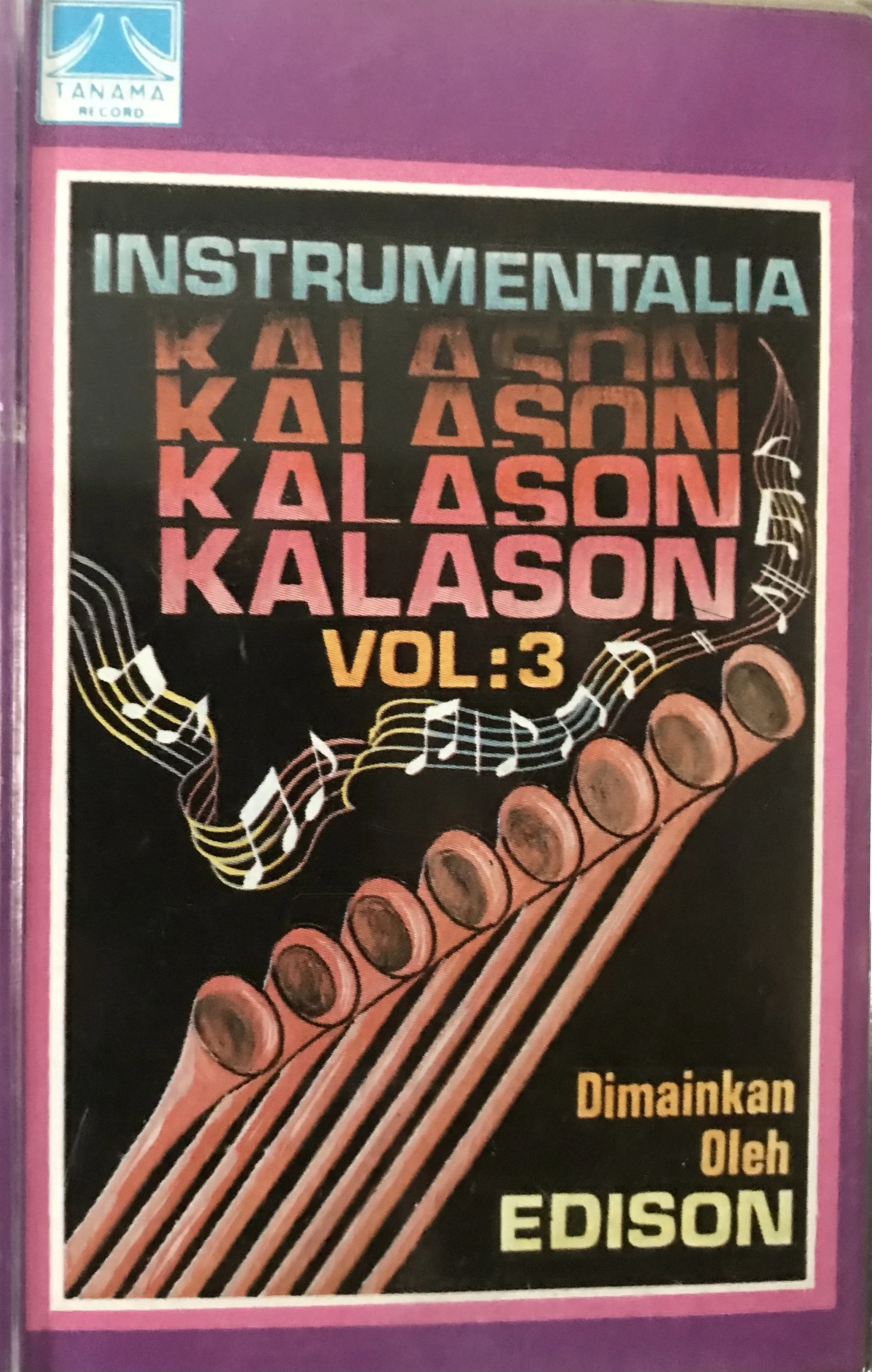

People loved the sound so much that some enterprising local record companies started putting out whole albums of kalason music, initially by recording actual bus horns like that of the famous Gumarang Jaya bus, and later with electric organ and synth sounds that imitated the kalason sound and style but with period pop backing tracks. Some musicians like Asben and Melati even became stars associated with the kalason sound despite not being from the bus world at all.

Pak Budahar continued playing and driving into the 1980s, when he finally retired to get married and settle down. The days of kalason were numbered, anyway, as times were changing. Larger, modern diesel buses started being imported from Japan in that decade, and the kalason apparatus didn’t work with these new engines. As the old Chevies were phased out, the kalason and the tukang who played them disappeared along with them. Pak Budahar estimated that the last of the buses with kalason probably drove their final routes in the early 1990s. Then, the music slumbered, living on only in cassette form.

In 2012, Pak Budahar was at home with his family in Alahan Panjang, a rural corner of Solok regency, when he heard the familiar musical toot of a horn outside. He went out to find not a bus but a revamped hot rod, a Chevy hardtop that a local car guy named Alfandi had tricked out with a working kalason. Pak Budahar recalled getting in and getting to hear the sound of the kalason come out from under the hood for the first time in decades. “All those years,” he said, “and I’d never forgotten.”

It was this new era of kalason revival that got my attention - after reading about the kalason phenomenon on Minangkabau historian Surya Suryadi’s blog, I was amazed to discover a grainy YouTube video of Pak Budahar playing “Sinar Riau” at a car show. Kalason lived! I was able to track down the name of the village and, years later, made it to Alahan Panjang to meet Pak Budahar and hear him play those old kalason hits while sat in Bang Alfandi’s tricked-out hot rod by the shores of Diateh Lake.

That was one of the most memorable musical experiences of a lifetime, not only getting to hear Pak Budahar play these old kalason tunes live but also sitting down and listening to his stories of bus life in the ‘60s and ‘70s. He sometimes seemed far away as he recalled those drives: “When I think of that time, I feel like going back.”

That era is long past, but I couldn’t help but get caught up in that nostalgic dream. I started scheming up a plan to this music on the road just like back in the day, driving across Sumatra with Pak Budahar as he played the kalason songs of his youth. For years, I held onto these recordings, thinking I’d develop this into something bigger - a documentary? A festival? With Pak Budahar in the front seat.

Only recently did I learn that Pak Budahar, already quite sick when I met him, passed away in 2023. One of the last tukang kalason of West Sumatra was now gone. It was Bang Alfandi who told me the news when I reached out to revive my schemes. Up to his last days, he told me, Pak Budahar was still playing the kalason, though his fingers had tensed up in his final years. “Now I still have the kalason,” Bang Alfandi lamented, “but nobody to play it.”

I can’t help but feel like one of those passengers looking in the rear-view mirror, watching something I love grow farther away, nearly disappearing on the horizon. Is kalason doomed to be an obscure historical footnote? There are still other tukang kalason out there, I’ve since discovered, and at least one other working instrument in Bukittinggi. I’m not sure of the kalason’s future, but for now, let’s take a moment to look longingly out the window as Pak Budahar’s kalason brings solace to our aching hearts.

+++

Special thank you to Bang Alfandi for graciously supplying the kalason and Pak Budahar’s children, especially Alung, for reaching out and giving their blessings for this post. And again, for the wonderful Pak Budahar - may your kalason sing forever.

From Hafiz Winaldo and Teti Darlenis’ fantastic paper “Fungsi Musik Kalason Oto Sebagai Hiburan Dalam Budaya Transportasi Masyarakat Sumatera Barat.”

Other great writing on kalason that inspired this post: my friend Luigi Monteanni’s “A Viral Horn for the Global Village,” Bart Barendregt’s “The Sound of ‘Longing for Home,’” Minang historian Surya Suryadi’s incredible blog.