Traces of Salindru in Banjar Lands: Gamalan Banjar in Barikin, South Kalimantan

I’m proud to share this guest post from Banjarbaru-based ethnomusicologist Novyandi Saputra. Novyandi, or “Nopi” as he is known, was the main organizer of my travels in South Kalimantan last year, and it was in his hometown of Barikin (a locus of gamalan Banjar) that we recorded his gamalan community, Sanggar Anak Pandawa. This post is purely the work of Nopi - yours truly (Palmer) provided translation and helped arrange the recordings, photos, and video. The piece has been shared as separate posts for Indonesian and English versions - to read the Indonesian version, click here.

+++

Gamalan Banjar’s long journey and roots in the Majapahit Kingdom is undeniable, as it is written in texts such as Hikayat Banjar: A Study in Malay History (Jj. Rass: 1968) and Wayang Banjar dan Gamelannya [Banjarese Wayang and its Gamelan] (Idwar Saleh: 1983/1984). Such texts have become an integral resource for peering into the era of gamelan’s arrival in South Kalimantan.

Turning to the text of Hikayat Banjar, on page seven, verse thirty-eight, it is explained:

“tah soedah kapaseban diboenjikan orang galaaijandjoer, maka radja kembali demikien djuga tatkala doedoek itoe dihadapan radja derie kirie tomonggong Tatah Djiwa diblakangnja itoe patih Baras dan patih Pasie patih Loeho patih doeloe diblakangnja itoe”. (Rass: 1968: 7)

“And so in the palace, the people played Galaganjur, heralding the king’s return. There before the King sat, on the left, Tomonggong Tatah Djiwa, behind him Patih Baras and Patih Pasi, proceeded still by Patih Doeloe.”

The word galaaijandjoer (galaganjur) in this quotation is a reference to one of the foundational pieces of the gamalan of the Banjar royal palace. It is in this text that we can see the first proof of gamelan’s presence [in South Kalimantan] since Empu Jatmika’s arrival and foundation of the Negara Dipa kingdom. To this day, the piece called Galaganjur is performed in both classical and folk gamalan Banjar traditions solely to accompany ceremonies involving the pembesar negeri (the king or respected guest) or, in some cases, traditional Banjarese wedding processions.

In his text on the history of gamalan Banjar, Idwar Saleh explains that Empu Jatmika and other royalty from Majapahit founded the kingdom of Nagara Dipa (located in what is now Amuntai, South Kalimantan) around the 12th century. It was in this era that we find the first arrival of Majapahit culture and its various artforms, one of which was the gamelan ensemble. Gamelan, it is said, was brought to Kalimantan along with wayang kulit (traditional shadow puppet theater) and topeng (masked dance) by Raden Sekar Sungsang. In addition to its use in Hindu religious ritual, gamelan of that era was played to accompany this wayang kulit and topeng, the function of which was to induce Banjarese society into embracing the Hindu religion and culture of Majapahit. (Saleh, 1984:1).

From its beginnings, gamalan Banjar consisted of two strains, the classical tradition of the Banjar royal palace (keraton) and the folk tradition (versi rakyatan). Fundamentally, the difference between these two traditions is rooted in the spaces in which they arose, with royal or classical gamalan constrained to the palace of the Banjar Sultanate while the folk tradition of gamalan Banjar grew amongst the commoners outside the bounds of the palace walls.

With the dissolution of the Banjar Sultanate in the era of Sultan Muhammad Seman in 1905, the royal gamalan Banjar tradition was inherited by descendants of the former nobility (keluarga pagustian). In addition to its inheritence by these noble families, gamalan Banjar continued to spread amongst the commoners, especially in combination with other folk arts such as the aforementioned wayang kulit, tari topeng, damar wulan (another form of folk theater with roots in Majapahit-era Java) and wayang gung (a theater and dance form called wayang orang in Java.)

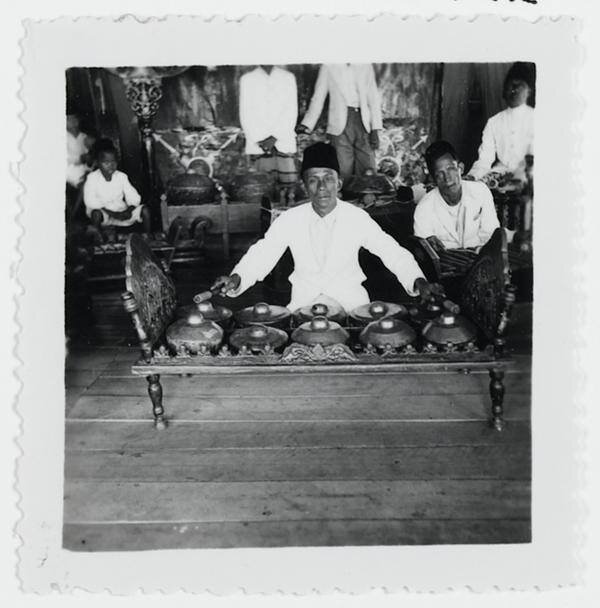

In this archival photo from the collection of the Troppenmuseum in the Netherlands, we can see an example of gamalan Banjar as it was played in 1905, with instrumentation consisting of sarun halus, gambang, babun, dawu, sarantam, agung halus, agung ganal, and katuk; other instruments such as sarun ganal, kanung, kangsi, and sarun paking were seemingly not in use. Of those instruments visible in the photo, all were likely made of bronze (gangsa, perunggu in Indonesian.) According to modern gamalan Banjar artisans and players, gamalan gangsa (bronze gamalan) soon fell out of favor with the decline in blacksmiths skilled in bronze work. From other clues in the photo, it is suggested that this particular performance was to accompany pantul alan-alan [a folk art in which masked dancers climb a wooden pole, similar to the national panjat pinang tradition still popular during Independence Day celebrations in Java.] The pieces performed were likely quite varied, with a busy dynamic suiting the context of folk performances.

Gamalan Banjar Simangu Kacil, said to be from the Negara Dipa era. At the Wayang Museum in Jakarta.

At a glance, gamalan Banjar bears a resemblance in form and character to gamelan in Java, with this resemblance especially clear in the case of royal gamalan Banjar sets such as Simangu Kacil and Simangu Besar. [Simangu Kacil is a relic of the 14th century Negara Daha kingdom, likely sent from Majapahit; also called Gamalan Laki, this set currently resides at the Jakarta History Museum. Simangu Besar is another royal gamalan set said to be a gift from the Sultan of Demak to the Banjar Kingdom in the 15th century; it currently resides in Kuin, in Banjarmasin.] Meanwhile, gamalan as made and played outside of the royal palace has undergone a number of transformations in material, construction, and number of instruments. According to Saleh’s research on the evolution of the folk gamalan ensemble, the dalang [puppetmaster] Raden Arya Tulur was the first to begin using iron (besi) instead of bronze in the construction of gamalan instruments, with this change emerging, as suggested before, due to the disappearance of artisans skilled in the production of bronze instruments.

Saleh classifies gamalan keraton/klasik (royal or “classic” gamalan), meanwhile, as gamalan which is played in the environs of the Banjar Sultanate in Banjarmasin and which is typified by its bronze instruments and “complete” instrumentation. With the passage of time, this royal gamalan has fallen out of popularity as it is rarely played, with the stewards of the dissolved Banjar Sultanate and its royal arts ever more lost to time.

The gamalan Banjar of the royal families remained quite complete for a time, as can be seen in this archival photo from 1938. At this time, these descendants of Banjarmasin’s nobility still maintained their gamelan to be played as an accompaniment to damar wulan theater. In the photo, we can see that the instruments of this royal gamalan still take the shape of rounded gongs (pencon) in comparison to the flattened metallophone variety (lampar) typical of iron folk gamalan.

In the modern day, the term gamalan Banjar almost always refers to gamalan in its folk form, as it is this form which has continued to spread and dominate the Banjar cultural sphere. Meanwhile, the gamalan Banjar of the royal palace has only recently been revived, as it was played once more by Sanggar Ading Bastari in 2012 to accompany the royal processions of the remaining nobility of the Banjar Sultanate.

Gamalan Banjar as it exists today has its locus in the production center of Barikin, a village in the Hulu Sungai Tengah regency of South Kalimantan. According to the author’s interviews with local historian and artist Sarbaini, Barikin has been the center of gamalan production and the source of the region’s most lauded dalang since the royal arts of the Nagara Daha and Nagara Dipa kingdoms were first brought out of the royal sphere by Datu Taruna, a historical nobleman (DAH. AW. Sarbaini, interview, 12 March 2015.) This suggestion is strengthened by Suriansyah Ideham’s statement that “by around 1525, Barikin had already become a center of arts under the leadership of Datu Taruna.” (2005: 397).

Gamalan Banjar as produced in Barikin uses a pentatonic tuning system called salindru Banjar. The term salindru itself stems from the roots of gamalan Banjar in Majapahit-era Java. Etymologically, salindru almost certainly stems from the Javanese term sléndro, one of the principal tonal systems used in Javanese gamelan or karawitan, especially those of Central Java. As Hastanto explains, sléndro is a pentatonic scale, that is, one which is made up of five tones. With this in mind, the salindru of gamalan Banjar can be said to be from the wider sléndro family.

Debate about the origins and arrival of gamelan in Banjar lands rage on in the present day. The data available to researchers of gamalan and other arts with roots in South Kalimantan’s early Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms are limited to the Hikayat Banjar (a legendary Banjar chronicle first transcribed by Dutch philologist Hans Ras in 1968) and the Tutur Candi, a historical text transcribed in the Arab Melayu script by Ramli Nawawi and translated by Mohammad Saperi Kadir, BA. These two texts, rooted in Banjar oral literary tradition, have become the primary references for researchers of Banjar history and culture.

This scarcity of written sources can be explained by the largely oral nature of Banjar culture’s literary tradition, as the history of gamalan Banjar have been passed down through spoken word from generation to generation, especially within certain gamalan families in Barikin. To this day, gamalan Banjar’s vitality rests in its place at the center of Banjar social life, from weddings (karasminan) to ceremonies such as manyanggar banua, a village cleansing ritual which still survives in Barikin.

This reconstruction of the historical path of gamalan Banjar is built on both the aural evidence of gamalan as well as evidence discovered through the course of the author’s research in the field. To be sure, this data remains imperfect and debateable. However, through this data we can begin to see the traces of gamalan Banjar’s journey of becoming, from gamelan to gamalan.